by Dr. William H. Thiesen, Coast Guard Atlantic Area Historian

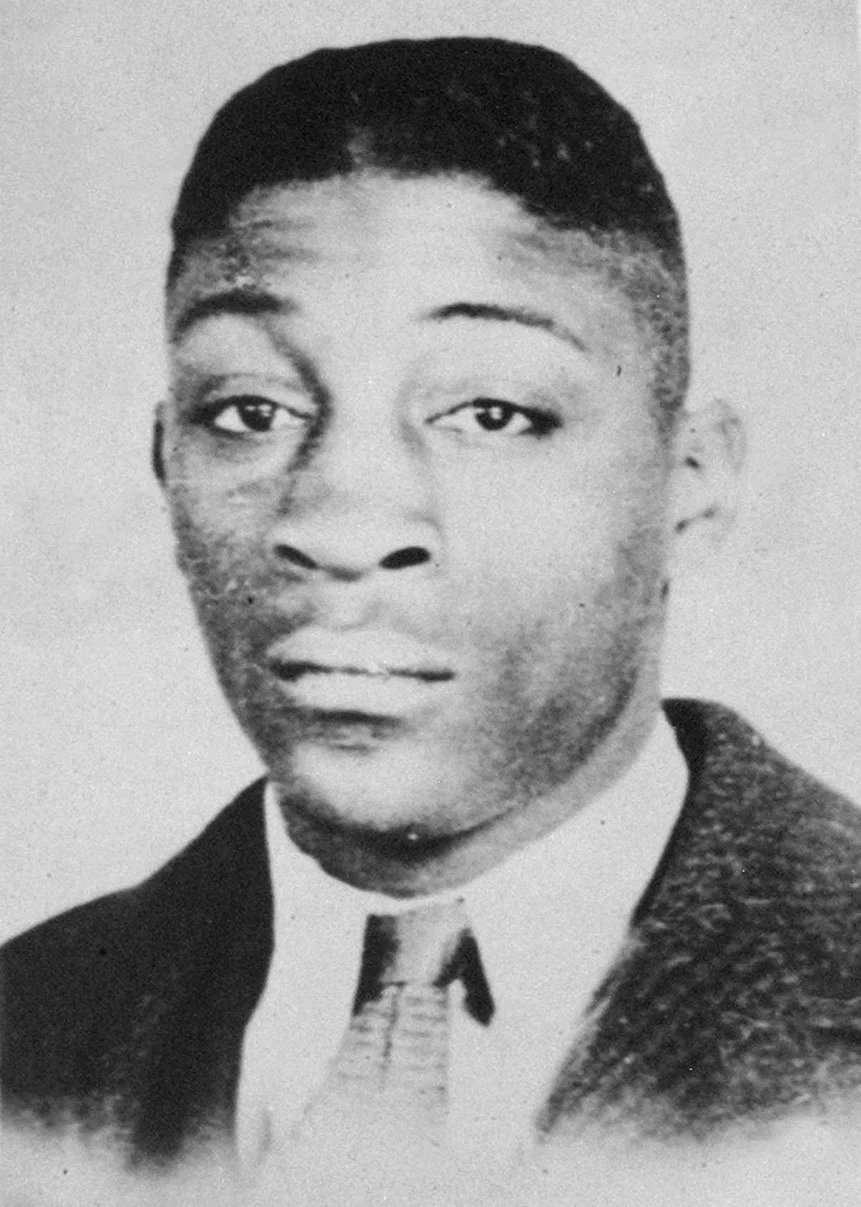

Mess Attendant Charles Walter David, Jr.

Many individuals need a lifetime to learn leadership skills. It comes naturally to others. Charles Walter David, Jr., namesake of Fast Response Cutter David, was an instinctive despite the racial barriers of society at the times. David served in the United States Coast Guard early in World War II, when the military services limited what African Americans were allowed to do and limited them largely to non-senior enlisted ratings.

Mess Attendant 1/c David was unique in every way. He reached the age of 26 during his time aboard the cutter Comanche in the Coast Guard’s Greenland Patrol and was one of the ship’s older enlisted crewmembers. At over six-feet-tall and 220 pounds, his stature intimidated others, but he still counted many friends among the cutter’s 60-man crew. He had a natural talent for music, playing the blues harmonica in jam sessions with shipmate and friend saxophone player Richard “Dick” Swanson.

What set David apart was the loyalty he had for his cutter and shipmates. This seems surprising given the second-class status that African Americans held in the Service at the time.

David demonstrated his character in February of 1943, while Comanche served as an escort for the three-ship convoy bound from St. Johns, Newfoundland, to southwest Greenland.

Weather conditions during the convoy’s first few days proved horrendous as they usually did in the North Atlantic winter. The average temperature remained well below freezing. The seas were heavy, and the wind-driven spray formed layers of ice on the cutter’s exposed decks and superstructure.

They fought both the elements and the German U-boats lurking in the frigid waters. At about 1 a.m. on 3 February 1943, U-223 torpedoed convoy vessel US Army Transport Dorchester, which carried over 900 troops, civilian contractors, and crew.

The task force commander ordered Comanche to screen rescue efforts. By the time they arrived, Dorchester had slipped beneath the waves and survivors had taken to the water and lifeboats. Comanche’s log noted, “all men in lifejackets lifeless.” However, when the cutter’s lookouts spotted lifeboats full of survivors, the crew threw a cargo net over the cutter’s port side. David, his friend Swanson and several shipmates swung into action clad only in un-insulated uniforms.

With waves 10 feet high, David climbed down the cargo net to the lifeboats and hoisted Dorchester’s living yet frozen victims to his shipmates on Comanche’s deck. Swanson worked alongside his friend saving nearly 100 survivors from the boats.

During the operation, Comanche’s executive officer, LT Langford Anderson, slipped and fell into the icy seas. Without hesitation, David plunged into water that could kill within minutes and helped Anderson back on board the cutter. After helping the last survivors up to Comanche’s deck, David climbed up the net. Six years younger than David, Dick Swanson lost use of his limbs and made it only halfway up the cutter’s side. David encouraged his friend, yelling “C’mon Swanny. You can make it!” But Swanson was too exhausted and frozen to go any further. David descended the net and, with the aid of another crewmen, pulled Swanson back up to the cutter’s deck.

R.W. Anderson (left), who was rescued by David, looks on while RADM S. V. Parker presents the Navy and Marine Corps Medal to Mrs. Kathleen W. David, and Neil David, the wife and son of Mess Attendant David.

Swanson later said Charles David was a “tower of strength” that day. He risked his life to save dozens of Dorchester survivors, Comanche’s executive officer and his friend Swanny. However, David harbored a deadly secret. Days before he had come down with a bad cold. The exposure to frigid water and sub-freezing temperatures turned into hypothermia.

When Comanche delivered Dorchester survivors to an Army hospital in Greenland, doctors ordered an ambulance for David as well.

It was the last time his shipmates would ever see him. His cold had turned into pneumonia. Within weeks he was dead. It took a few weeks before his shipmates learned that their friend had died.

David was temporarily buried in the permafrost of Greenland. After the war, the military re-interred his remains in the Long Island National Cemetery at Farmingdale. It was 60 years after his heroic end that the Service undertook a systematic search for his immediate family and notified his next of kin of his gravesite.

Despite his secondary status in a segregated service, Charles Walter David, Jr., placed the needs of others before his own. For his heroism, David was posthumously awarded the Navy & Marine Corps Medal and, in 1999, was recognized with the Immortal Chaplains Prize for Humanity.

Recently, the United States Coast Guard named a Fast Response Cutter in his honor. David was a true Coast Guardsman and one of the Service’s long blue line, who exemplified the Coast Guard’s core values of honor, respect and devotion to duty.

Charles David Jr., is the first Sentinel Class Fast Response Cutter to be homeported in Key West.